Do you believe that, in order to make an electronic payment in the United States, first you should have to loan money at 0% to a venture capital firm, a billionaire real estate mogul, or a rich law partner looking to buy a second vacation home?

Most people would answer “no” to this question.

So if I told you that the answer to this question in the current American financial system is actually “yes”, how would you feel about that? What if I also told you the current rules mean you are not allowed to have another option, and you are trapped?

How Things Work Part 1: Banks, Simplified

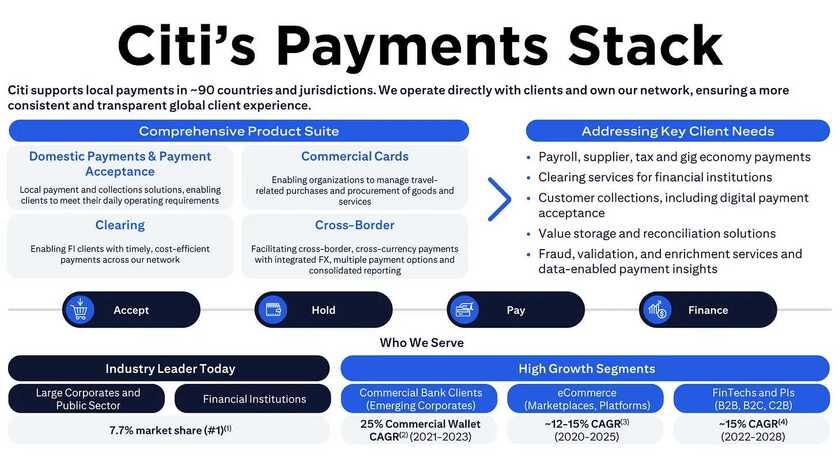

The starting point for most payments in the United States is a bank account. While there are rare exceptions to that system, for the overwhelming majority of retail payments (and many corporate payments), the starting point is the humble checking account.

So what happens with that thing? From the perspective of the customer, it’s simple: you give money to your bank to put it in that account, it’s there, and when you need to pay bills or buy stuff, you spend it. How? Debit card, check, cash at an ATM, having your credit card paid off by the funds, etc. It’s all pretty simple. If you want to be simultaneously fancy and live in like 1948, you can send a wire.

Now, that is the customer perspective, so here is the more interesting question. What happens on the bank side when you deposit money into your checking account?

Banks receive deposits, and they become liabilities of the bank. This is important to understand, as it is very much not the case that the bank just keeps that money, set aside, segregated, as purely the property of the person who gave that to them. That is a custodian. The bank, more specifically, is taking your money and can do whatever they want with it. What do they pay you for that privilege?As of August, 2023, the national average is 0.42%.That is not a typo. In an environment where the Federal Funds target rate is 5.25%-5.5%, banks are paying through an average of 0.42% on your checking account, meaning even if they lend risk-free to the government, they are pocketing 5% for letting you give them money, and then giving you a tiny amount. If they lend that onwards to billionaires and venture capital firms, they keep even more of the spread, and still pay you the same amount.

So let us pause for a moment and ask a simple question: is that a fair price to be granted the privilege of being allowed to pay people for things?

How Things Work Part 2: When Things Break

If the story ended there, it would be a simple conversation about what the price of access should be. There are many viable answers to that question: zero, some small amount, or several percentage points of your money every year, such as in the current system. The story does not end there, however. Remember that part where you deposited money to the bank and they start doing things with it? Those things typically involve taking credit risk to people they have lent money to, and also taking duration risk to the term of those loans if rates rise. Let us just say that banks have a history of getting themselves into trouble with those kinds of risks, to put it gently.

This means that, for the average person, you are putting money into a black box, and then praying the box does not explode and you lose all your money. We have the FDIC in the United States precisely because of this problem, but that covers you up to $250k. More than enough for a small individual account, but what about a regular business just taking payments? Is that enough for, say, a grocery store? How about a Best Buy location? Do we really expect Wal-Mart to have 54,182 bank accounts just to avoid credit risk? At that point, Wal-Mart should literally just start their own bank (some companies have done this!). In short, once you incorporate credit risk, now you are essentially both paying a huge subsidy to rich borrowers who are the borrowing from a bank and essentially selling the bank CDS protection for free on all funds over $250k, just to be allowed to use the payments system. Yikes.

How Things Work Part 3: Timing and Tracking

Another problem with the current banking system is that it is (unnecessarily) slow.

Electronic signals move very quickly, yet somehow wiring money around the world takes 4+ days and is subject to the whims of banks and completely non-transparent. If you send money from the United States to a relative in Hong Kong, what is the pathway the money takes to get there?

You don’t know, do you?

This is completely unnecessary. Many of these delays are due to regulatory compliance, but many of them are also simply due to oligopoly power of banks and delaying things so they can make extra money on the friction.

What this does do is create a web of confusion and opacity for the average user. Sending money to a relative overseas (or even just at another domestic bank!) currently means you are going to not exactly know where your money is for an unclear amount of time with no real understanding of if/how/when errors occur. Also, you’re not earning any interest (not that most banks are paying you anyways) on that money while it is in flight.

Does this seem fair?

What is a Stablecoin?

For those who have read my work elsewhere, we are going to come back to a familiar definition that I have used repeatedly.

A Stablecoin is a unit of fiat currency represented on a blockchain.

For such a simple statement, there is a lot that is said. Ignoring the issues of designing a stablecoin properly for now, let us just simply say this is a US dollar stablecoin backed only with transparently disclosed reserves of very short dated t-bills. That’s something that almost everyone (banking regulators, the SEC, FASB, etc.) agrees trades at $1. So what happens when that thing exists?

First, it removes the problem of subsidizing risky borrowers. Depending on the design of the stablecoin, and whether it is interest paying or not, you may be subsidizing the government. However, what you are not doing is lending that money to the usual suspects that banks lend it to. Lending solely to the US Treasury, while still perhaps something that could end badly, is at least within the realm of basic expectations for holding money. People will not be surprised when their US dollar stablecoin is impacted if there are stability problems for the dollar itself.

Second, it removes the black box problem of bank solvency. In addition to not subsidizing risky borrowers, now you are not also staring at a horrible black box that contains a mix of mortgage lending, corporate lending, underwriting and issuance, prop trading, asset management, prime brokerage, and who knows what else just to use the payments system. A very vanilla, narrowly designed stablecoin means solvency comes down to two simple factors: one, is the stablecoin company run by idiots who make catastrophic operational errors (no escaping this one for any company) and two, is the US government itself solvent? This, I might suggest, is at least something you can try to reasonably assess from the outside. If your stablecoin holds reserves bankruptcy remote, even the first issue isn’t fatal to you, just annoying.

Third, you have solved the transfer problem. Sending money on a blockchain is near instantaneous. In fact, it’s downright miraculous compared to the four day journey of my friend Omid’s international wire. Similarly, it’s quite cheap, if you use the right chains. This means that you know where your money is up until the point that it vanishes from your wallet and appears in that of the recipient, at which case you can see it has been delivered. You know what this doesn’t allow for? Four days of delays, games, and correspondents fighting with each other at your expense to scrape basis points of interest.

So we’ve gone from subsidizing billionaires building commercial real-estate, expecting plumbers, nurses, schoolteachers, and grocery store chains to perform their own due diligence on global megabanks to ensure their funds are safe, and allowing intermediaries to deliberately gum up the system or just refuse to innovate to delay payments for their own benefit and/or laziness, to a system that is instant, transparent, and puts people in control of their own money.

Is it any wonder that the entire financial system fucking hates it?

Competition

There is nothing that incumbents with special privileges hate more than fair competition. Certainly, this is part of the hysterical reaction to blockchain technology and the driver of banks and certain bank advocates and regulators to the innovation. From the perspective of banks, this is an existential threat to their business: zero cost, instant transactions without the need for an intermediary would wipe out entire (very profitable, because they have a monopoly of economic force) business lines. More so, it would have a fundamental impact on the profitability of the entire industry. Multi-million dollar bonuses are at stake, you see. In short, stablecoins represent a full front assault on the traditional arrangement that even something like the Narrow Bank could not quite achieve, because it did not have the connection to a blockchain and the many-to-many payments network attached. At the core, this represents a complete re-negotiation of the financial structure of our payment system. A system based on stablecoins of this sort means:

Users of the payment system do not subsidize borrowers implicitly

Users of the payment system do not have to understand or try to evaluate black-box complex financial entities just to make electronic payments

Legacy payments systems built on intermediaries and delays cease to exist

Is this not a strictly better system for the average user?

Yes, large borrowers will pay higher costs for debt (is this bad?). Yes, many large banks will become significantly less profitable (is this bad?). However, the average person takes less credit risk, has more control of their funds, and can send their money when they want, to who they want, for virtually zero. More so, customers of this sort are much cheaper to deal with. The entire cost burden of banks is virtually gone with regard to payments. Now, anyone who can create an electronic wallet and deposit funds is formally part of the system. From a financial inclusion perspective, you don’t have to worry about their credit, you don’t have to worry about compliance to the same degree. The entire cost structure is, well, deconstructed.

What does this mean? The kinds of customers that are unprofitable and get terrible service or worse, no service at all from banks? Now they can also be fully integrated into the system.

I suggest this is important.

Time Ends All Monopolies

This progress is inexorable. Forty years from now, we will not be transacting with an opaque, highly centralized, extremely expensive system when the technology and economic incentives to do better exist. However, one prediction I will make is that the places that will embrace this first are actually the ones who are the furthest behind now. Just like Africa, in many cases, went straight to mobile phones and skipped the landline, payments systems will likely evolve in areas with rickety or poorly run financial systems first.

Yes, the marginal benefit of this system in the United States is real, but it’s marginal. This benefit in Argentina, where you could get on a global, fast, secure, peer to peer omni-ledger and use dollars to avoid the local inflation of 100% per annum that has been running for decades? I’m no rocket scientist, but that seems pretty compelling.

Once that happens, then technology will begin to bleed backwards. If you trade with people who are doing that, why stay on the old system? It begins to flow downstream to the places that were slower to adopt. Right now, most Western nations face the nation-state equivalent of the innovator’s dilemma with regard to this, so they may very well go last. Just like the disrupted companies often move last and get run over as a result.

But it will happen, eventually.

The question is just if someone else will go first, and seize an outsized share of the economic pie as a result.

Brought to us Courtesy of Dinelle Dixon from The Stellar Foundation:

All while Pfizer—a company with a $2.3 billion criminal fine for fraudulent marketing, bribery, and kickbacks—was given blanket immunity from liability and billions in taxpayer dollars to produce a vaccine in record time with no long-term safety data.

All while Pfizer—a company with a $2.3 billion criminal fine for fraudulent marketing, bribery, and kickbacks—was given blanket immunity from liability and billions in taxpayer dollars to produce a vaccine in record time with no long-term safety data.