Last year a dear friend was diagnosed with an aggressive cancer, and in spite of her grim prognosis, she is doing very well and her cancer seems to be in remission. One of her approaches to fighting the illness has been a restricted diet with little sugar.

In a recent conversation with my friend Nate Jones—CEO of XLEAR Nasal Spray—he drummed the table for me to read Otto Warburg’s papers on the relationship between cancer and sugar. I’d been meaning to do so for some time but never seemed to find the time. And then, this evening, I saw a report in the Epoch Times whose headline caught my eye: How Sugar Fuels Cancer in the Body.

Immediately I thought, “Wasn’t this Warburg’s thesis way back in the 1930s, just as Nate was recently telling me?” I quickly read the article and noted this paragraph:

Cancer cells require a substantial amount of glucose to survive. In the 1930s, Otto Warburg, a German biochemist, discovered that both cancer cells and normal cells require sugar, but their metabolic pathways differ: Normal cells primarily convert glucose into energy through aerobic respiration, while cancer cells obtain energy through glycolysis instead of using oxygen.

As Warburg put it:

Cancer, above all other diseases, has countless secondary causes. But, even for cancer, there is only one prime cause. Summarized in a few words, the prime cause of cancer is the replacement of the respiration of oxygen in normal body cells by a fermentation of sugar.

In many respects Warburg reminds me of the Viennese philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. Both men seemed to have an effortless way of grasping complex things, and both were instantly recognized for their sparkling intellect.

In spite of being gay and Jewish on his father’s side, Warburg was completely left alone by the Nazi regime. Hitler—who’d been terribly traumatized by watching his beloved mother waste away from breast cancer—was apparently obsessed with ascertaining the cause of cancer, and word had it that if anyone could figure it out, it was Warburg.

It was in this same era that that the German physician and researcher, Dr. Fritz Lickint, published a meta-analysis of 167 reports linking smoking to lung cancer. He published his study a full twenty years before Sir Austin Bradford Hill published his epidemiological study of the link between cigarette smoking and lung cancer. That the American tobacco industry and it hired gun scientists were able to suppress Lickint’s findings for over forty years is a testament to mesmerizing power of money.

The Wikipedia article on Otto Warburg proposes that he was observing an effect cancer, and not the cause. As the Wiki entry puts it:

Today, mutations in oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes are thought to be responsible for malignant transformation, and the metabolic changes Warburg thought of as causative are now considered to be a result of these mutations.

This strikes me as a bit too neat, and I wonder if the marked change in the metabolic preference of cancer cells for glucose is an expression of something deeper that isn’t fully understood.

It also reminds me of a recent study by Nakahara T, Iwabuchi Y, Miyazawa R, et al. titled "Assessment of Myocardial 18F-FDG Uptake at PET/CT in Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2–vaccinated and Nonvaccinated Patients"

Perhaps it’s just an association of ideas, but as I read about Warburg’s reflections on cancer and glucose, I immediately thought of Nakahara’s conclusion:

In conclusion, in a set of patients who underwent PET/CT for indications other than myocardial inflammation, those who had received a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine showed increased myocardial fluorine 18 (18F) fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake on images up to 180 days after their second vaccination compared with patients imaged before SARS-CoV-2 vaccination was available. Vaccinated patients showed higher myocardial 18F-FDG uptake on PET/CT scans compared with nonvaccinated patients, regardless of sex, age, or type of mRNA vaccine received.

This finding strikes me as super weird. For those unfamiliar with FDG, it is defined as follows:

Fludeoxyglucose F18 is a radioactive tracer that acts as a glucose analog and is used for diagnostic purposes in conjunction with positron-emitting tomography (PET) to localize the tissues with altered glucose metabolism. It does not have therapeutic use. Altered glucose metabolism has implications for malignancies, epilepsy, myocardial ischemia, inflammatory conditions, and Alzheimer disease.

I don’t have the training to interpret the implications of Nakahara’s conclusion, but I strongly suspect that it does not bode well. I welcome comments from specialists in this field of research.

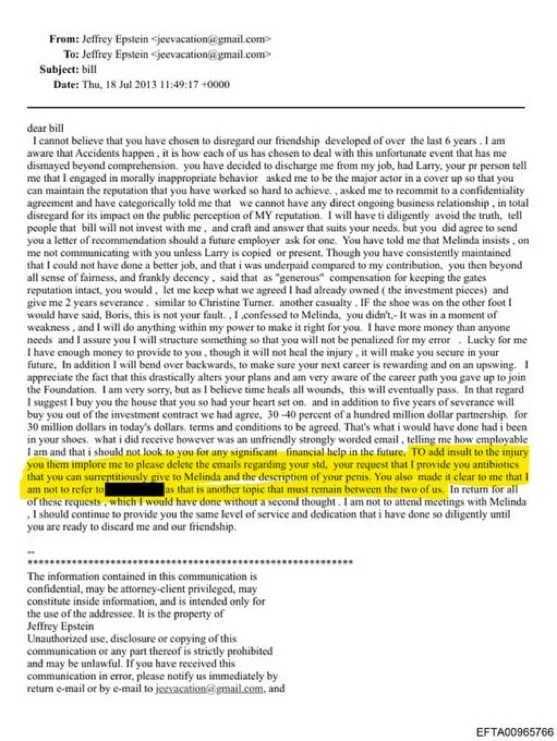

All while Pfizer—a company with a $2.3 billion criminal fine for fraudulent marketing, bribery, and kickbacks—was given blanket immunity from liability and billions in taxpayer dollars to produce a vaccine in record time with no long-term safety data.

All while Pfizer—a company with a $2.3 billion criminal fine for fraudulent marketing, bribery, and kickbacks—was given blanket immunity from liability and billions in taxpayer dollars to produce a vaccine in record time with no long-term safety data.