As recently as the 1960s, securities settlement was strictly physical.

When a stock or bond traded, a paper certificate had to be physically moved from seller to buyer, typically by retired policemen, firefighters, and others crisscrossing lower Manhattan with stacks of bearer securities.

Delivery wasn’t considered final until those couriers returned to confirm they had not been mugged along the way or forgotten their satchel of stocks, bonds, or cash on the subway.

A surge in trading activity after 1965, however, flooded Wall Street with more trades than its brokerage houses could manually process, leading to the “paperwork crisis” of 1967 — the only time in history when back-office operations made newspaper headlines.

The crisis forced exchanges to close on Wednesdays, shorten trading hours on other days, and extend settlement to T+5 — all in an effort to allow brokerages to work through their backlog of unsettled trades.

But that, too, failed to stem the tide — chaos and disorder continued to reign to such a degree that $400 million of securities were said to have gone missing, including $900,000 of IBM certificates stolen by a 22-year-old back-office clerk.

The crisis finally subsided when the bear market of 1969 lowered trading activity to a manageable amount, but the damage was done: In subsequent years, many investors self-custodied their security certificates because when brokerages failed — as many did during the crisis — the securities they held for customers were prone to go missing.

The legacy of the paperwork crisis, however, is the Wall Street that we know today: computerization, NASDAQ, centralized clearing, and giant brokerages (that could afford the new systems) are all direct consequences of the backoffice chaos of 1968.

As self-evident as all those things seem, it took a crisis to make them happen.

A recent paper, Electronification, trading, and crypto, suggests blockchain-based exchanges are now equally self-evident.

But it might take a crisis to make that happen, too.

Dematerialized

In addition to the paperwork crisis, the authors of Electronification cite two further incidents of financial crisis begetting financial innovation.

While the 1960s chaos forced investment banks to adopt computers and retire physical delivery, it took an exogenous shock to do the same for commercial banks.

Prior to 9/11, when a check was deposited at a bank, the bank would mail it to the Federal Reserve where it was sorted and sent in a batch to the bank the check was drawing on.

It took as much as two weeks for a check to clear.

But when the US government grounded air travel for several days in response to 9/11, checks, because they could not be mailed to the Fed, could not clear at all.

That made the antiquated nature of the payments system painfully clear, but it still required Congressional intervention to force retail banks to change: The Check 21 Act of 2003 forced banks to accept electronic images of checks in lieu of physical checks, dragging the payments system into the computer age.

It’s for that reason that you now probably deposit checks, on the odd occasion you get one, on your phone.

Similarly, it took an act of God to get Wall Street to finally abandon physical share certificates.

The paperwork crisis led to the founding of the DTCC, a central clearing house to hold everyone’s securities so they wouldn’t have to be messengered around after every trade.

But many of those securities continued to be held in physical form — enough so that when Hurricane Sandy flooded lower Manhattan in 2012, 1.3 million security certificates (worth trillions of dollars) held by the DTCC in an underground vault were soaked to ruin.

This prompted the DTCC to speed up the “dematerialization” of US securities, although, even today, a small fraction of securities continue to be held in physical form.

Be ready

That any securities at all still exist in physical form may be evidence enough that the financial system is overdue for another radical overhaul.

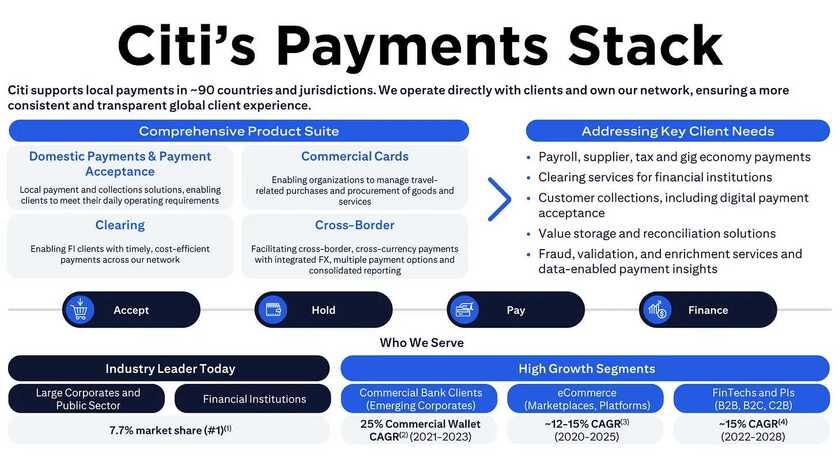

The authors of the Electronification paper think blockchains are the obvious next evolution of markets, in part because they would allow “the entire trading stack [to be] integrated into a single cohesive system."

It makes sense: The DTCC holds our US securities because physical delivery made self-custody unfeasible in the 1960s, but blockchain-based exchanges would let us both self-custody the assets we buy and deliver them instantly when we sell — and do all kinds of new things in between.

History suggests, however, that it will take a headline-worthy disaster to make it happen.

Most people are blissfully unaware as to who holds their securities for them, so unless North Koreans hack the DTCC or the DTCC’s databases are wiped out by a solar flare, it’s hard to imagine the finance industry spending the many, many billions of dollars it would take to radically upgrade the current system.

But history also suggests that legacy systems don’t last forever.

So, whenever the next disaster in market structure hits, blockchain-based exchanges should be ready to ensure the crisis does not go to waste.

All while Pfizer—a company with a $2.3 billion criminal fine for fraudulent marketing, bribery, and kickbacks—was given blanket immunity from liability and billions in taxpayer dollars to produce a vaccine in record time with no long-term safety data.

All while Pfizer—a company with a $2.3 billion criminal fine for fraudulent marketing, bribery, and kickbacks—was given blanket immunity from liability and billions in taxpayer dollars to produce a vaccine in record time with no long-term safety data.