The headline is our summary of a longer question about stablecoins raised by Agustín Carstens, the General Manager of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) during a BIS conference in Mexico last week.

Following a panel entitled, “Is there a role for cryptocurrencies?”, Mr Carstens posed the question to Berkeley academic Christine Parlour:

“Do you think that a lot of the traction that crypto is gathering has to do with the fact that traditional finance and traditional money has not evolved at the speed of technology and responded to what people need?

So let me put (it) one way. If we had, for example, a wholesale central bank money or reserve currency, technologically advanced, do you think that could make up for the demand for stablecoins.

For example stablecoins – one of the reasons why I don’t like (them) is that when you talk about money, if you need to put as a previous adjective “stable”, that tells you there is something wrong or there is some vulnerability there. Now stablecoins are backed by US Treasuries or by cash, which at the end of the day is the ‘real thing’. So, shouldn’t we concentrate more on making the ‘real thing’ to be able to be represented technologically in such a way that the space that stablecoins or crypto is filling would be filled in a more solid way?”

CBDC and a matter of trust?

Ms Parlour responded:

“It all comes down to trust. So if you have a world where everyone trusts Tether and everyone uses Tether to make payments, it’s very difficult to see why anyone would switch at this point to something that is issued by one central bank. If it is in fact the case that these stablecoins are used internationally then why should I care about central bank A when I’m in jurisdiction B.

Why not just take this large international company that seems to be multinational and doesn’t seem to have sort of strange biases. So I think at this point it’s very very difficult or it will be difficult for central banks to come up – with some dramatic exceptions – central banks to come up with a widely adopted stablecoin that basically could overtake things like Tether.”

Her reference to CBDC “exceptions” included a literal nod to moderator John Rolle, who is Governor of the Bank of Bahamas, which has issued a retail CBDC.

Retail v wholesale CBDC …

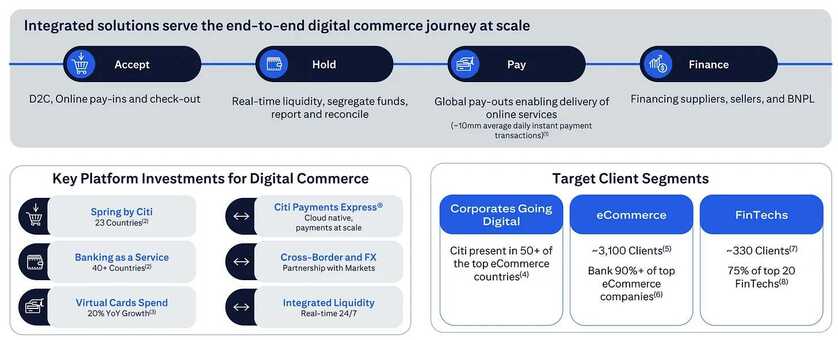

Mr Carstens wasn’t referring to retail CBDC. He was talking about wholesale CBDC to be used between banks to empower cross border tokenized deposit payments. The BIS currently is running Project Agorá with seven central banks and 41 institutions.

We’d observe that switching is only an issue if stablecoins are already pervasive in the mainstream.

So far stablecoin transactions are mainly used in crypto. PayPal’s Jose Fernandez da Ponte was asked during a Congressional hearing this week about the proportion of remittances that use stablecoin payments. He responded that it would be a low single digit percentage.

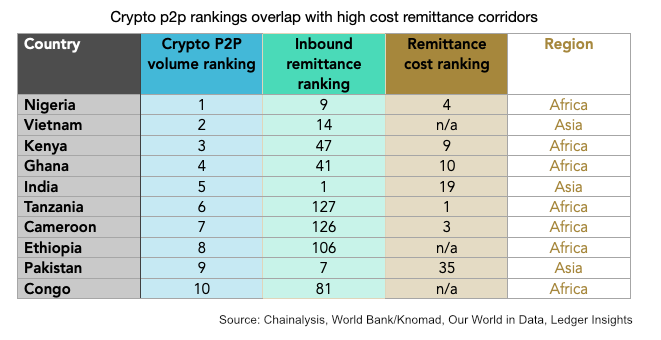

The other use case with some traction is people in economies with weak currencies, which also tend to overlap with regions where cross border transaction costs are high. P2P payments are more likely to be real world, so the graphic below shows the regions where P2P payments are more prevalent. There’s a fuller discussion in a recent report on bank stablecoins and tokenized deposits.

Hence, while stablecoins are making headway in cross border payments, they are not pervasive. Yet.

Three reasons for the lack of traction have been usability, a lack of infrastructure and integration, and regulation. All three are falling away, which is why there’s so much excitement in the space at the moment. On the infrastructure front, Stripe’s acquisition of Bridge is a strong signal, but there are many others.

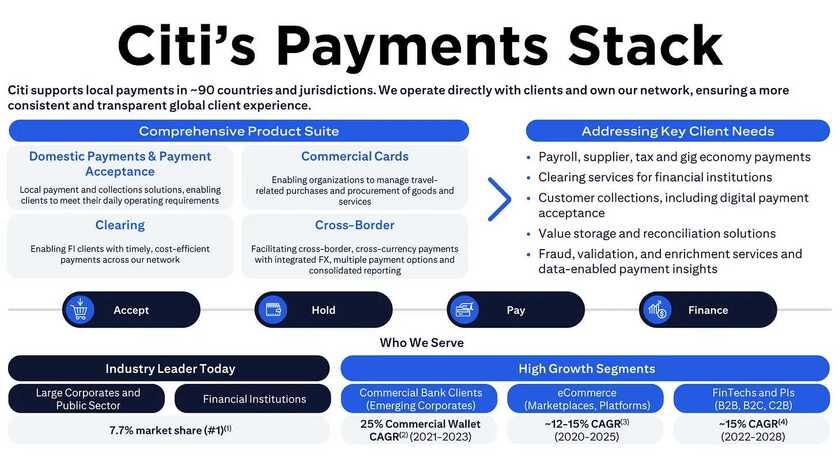

Can banks save their turf?

That’s not to say that one or more wholesale CBDC solutions will be the foil to stablecoins. How likely are banks to tackle the payment corridors in the above graphic at an early stage?

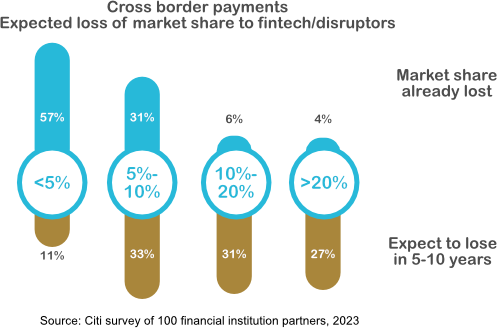

But the biggest challenge is the lack of urgency in banks because of an under appreciation of the threat. That’s illustrated in this 2023 Citi survey, where only around a quarter of institutions thought they might lose more than a 20% market share during the next five to ten years.

All while Pfizer—a company with a $2.3 billion criminal fine for fraudulent marketing, bribery, and kickbacks—was given blanket immunity from liability and billions in taxpayer dollars to produce a vaccine in record time with no long-term safety data.

All while Pfizer—a company with a $2.3 billion criminal fine for fraudulent marketing, bribery, and kickbacks—was given blanket immunity from liability and billions in taxpayer dollars to produce a vaccine in record time with no long-term safety data.