Every warning. Every documentary. Every article. Every post that got us banned. All of it was true. Now what? What can we do? Read on, share this Substack, help us save lives! The Light is shining! ✨

Well, well, well… look what the cat dragged in.

Actually, scratch that. Look what the Department of Justice finally dragged out of Jeffrey Epstein’s email inbox and dumped on the world’s doorstep like a rotting corpse nobody wanted to claim. Yep, that’s right. The Epstein files. It’s hilarious how the “Democratic hoax” and “fantasy” client list we were all told didn’t exist suddenly became a very real, very unsealed document.

For years—years—they called us conspiracy theorists. They slapped “misinformation” labels on our posts faster than Pfizer could print liability waivers. They kicked us off platforms, lied about us in the media, and shadow-banned our reach. Meanwhile, the real conspiracy—the one typed out in black-and-white emails between billionaires, bankers, and a convicted pedophile—was sitting in a government vault, waiting to prove us right.

And now? Now the receipts are public.

The release of Jeffrey Epstein’s files has done far more than expose a network of elite pedophilia and blackmail—it has vindicated truth-tellers like us and countless others who were smeared, censored, de-platformed, and persecuted for warning about the sinister agendas of the globalist elite. The documents reveal shocking connections between Epstein, Bill Gates, pandemic planning, and the systematic suppression of anyone who dared to connect the dots.

We weren’t crazy. We were just early. And they hated us for it.

Epstein, Gates, and the Pandemic “Business Model” They Built Together

One of the most damning revelations from Epstein’s files is his partnership with Bill Gates. Forget the carefully crafted PR spin about “regretting” those meetings. These weren’t casual dinners. These were planning sessions.

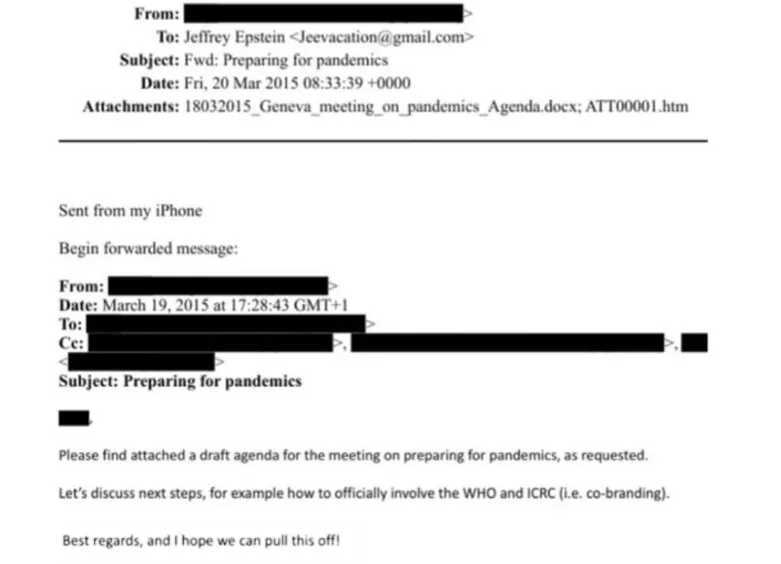

Back in 2015, Gates and Epstein exchanged emails about “preparing for pandemics” and strategies to “involve the WHO.” Gates wrote: “I hope we can pull this off.”

How’s that for a chill down your spine?

This eerily foreshadowed the 2019 Event 201 simulation—a pandemic exercise hosted by the Gates Foundation, Johns Hopkins, and the World Economic Forum that just happened to model a global coronavirus outbreak… just months before COVID-19 ”mysteriously” emerged in Wuhan. Funny how that works, isn’t it?

But let’s rewind even further, to the real blueprint—the financial architecture that made the pandemic response not just possible, but profitable.

The story crystallizes in a chilling 2011 email exchange. Juliet Pullis, a JPMorgan executive under then-chairman Jes Staley, emailed Jeffrey Epstein with a list of detailed questions. The source? “The JPM team that is putting together some ideas for Gates.”

The questions were precise: What are the objectives? Is anonymity key? Who directs the investments and grants? This wasn’t JPMorgan consulting an expert; it was a trillion-dollar bank asking a convicted felon to architect a billion-dollar philanthropic fund for Bill Gates.

This wasn’t JPMorgan consulting a philanthropic expert. This was a trillion-dollar bank asking a convicted felon to architect a billion-dollar philanthropic fund for one of the richest men on Earth. Let that marinate for a moment.

Epstein’s reply was fluent and commanding. He described a donor-advised fund with a “stellar board” and ties to the Gates-Buffett “Giving Pledge.” He noted the billions already pledged and identified the gap: “They all have a tax advisor, but have no real clue on how to give it away.” His solution? “JPM would be an integral part. Not advisor… operator, compliance.“ Staley’s response: “We need to talk.”

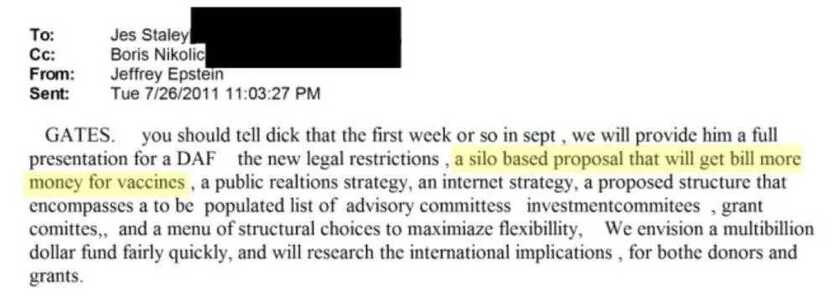

By July 2011, the plan evolved. In an email to Staley, copying Boris Nikolic (Gates’ chief science advisor), Epstein laid out the core pitch: “A silo based proposal that will get Bill more money for vaccines.”

Not “more research for pandemics.” Not “better public health infrastructure.” “More money for vaccines.” This is the unambiguous language of capital formation, not charity. It reveals the structure’s intended output planning reached the highest levels.

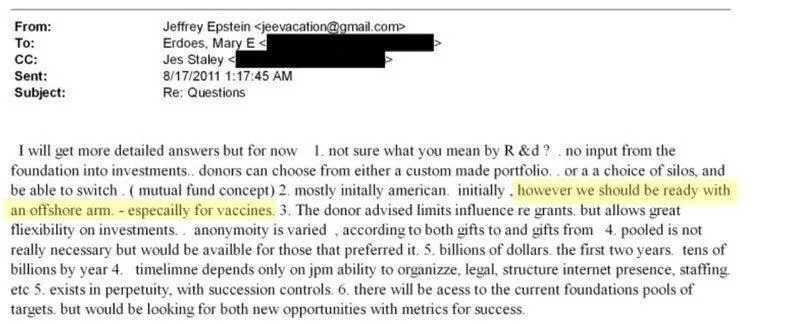

In August 2011, Mary Erdoes, CEO of JPMorgan’s $2+ trillion Asset & Wealth Management division, emailed Epstein (while on vacation) with additional operational questions.

Epstein’s reply was breathtaking in scope:

Scale: “Billions of dollars” in two years, “tens of billions by year 4.”

Structure: Donors choose from “silos” like mutual funds.

The Kicker: “However, we should be ready with an offshore arm — especially for vaccines.”

An offshore arm. For vaccines. For a charitable vehicle. Let that sink in.

So, by the time the world was panicking in March 2020, the financial machinery was already built. The investment vehicles, the donor-advised funds, the reinsurance products at places like Swiss Re, and even the simulation playbooks were dusted off and ready to go.

The pandemic wasn’t an interruption to their business—it was the Grand Opening.

Epstein’s role extended far beyond trafficking; he was a facilitator and blackmail operative for the global elite. The same forces that orchestrated the COVID-19 power grab—the mask mandates, lockdowns, censorship, and coercive mRNA push—are the ones who silenced critics like us.

Gates, despite his documented ties to Epstein (multiple flights on the “Lolita Express” after Epstein’s 2008 conviction), walks freely. He’s on TV. He’s advising governments. He’s still funding “global health initiatives” and pushing digital IDs, vaccine passports, and climate lockdowns.

Meanwhile, people like our friend, Joby Weeks, are under house arrest without charges, and voices like ours were de-platformed, demonetized, and destroyed for saying this very thing.

We told you. You knew it in your gut. Now you have the emails.

Censorship: The Elite’s “Misinformation” Label to Cover Their Crimes

The Epstein files expose not just criminal behavior, but the playbook for the systematic suppression of truth. While Epstein’s powerful friends were being protected by the FBI, the DOJ, and the media, platforms like Facebook (Meta), YouTube (Google), and Twitter went to war against anyone talking about it.

Think about the sheer audacity.

We were banned from social media for calling COVID-19 a “fake pandemic” and exposing the vaccine injury data that’s now undeniable.

Below is a screenshot of the first Facebook post that was taken down and then used as “Exhibit A” in their “reports” about how bad we were, naming us the 3rd most dangerous people on earth after Dr Joseph Mercola and Bobby Kennedy in the digital hit list they called the “Disinformation Dozen.” They attacked us, lied about us, and pressured the media, social media, and population at large to do the same: attack, threaten, and cast us out.

We were labeled “dangerous” for sharing emails, documents, and research that the DOJ and the CDC have now confirmed.

It was never about “safety.” It was about narrative control.

The same institutions that turned a blind eye to Epstein’s crimes for decades—the same ones that let him “commit suicide” in a maximum-security prison with cameras conveniently malfunctioning—suddenly became the ruthless hall monitors of “acceptable discourse,” ensuring only their approved stories could be told.

Big Tech, Big Media, and Big Government are all part of the same protection racket. They shielded Epstein’s client list, and now they shield the architects of the pandemic debacle. Independent journalists, researchers, and health advocates like us, who connected these dots, were systematically de-platformed, demonetized, and destroyed.

Why? Because we were right, and that was the greatest threat of all.

When you’re over the target, that’s when the flak gets heaviest. And brothers and sisters, we were getting shelled.

They Lied About Us While Protecting the Real Criminals

Let’s be crystal clear about what happened here.

We have spent decades exposing the cancer industry, Big Pharma’s corruption, and the suppression of natural health solutions. We produced The Truth About Cancer docu-series, reaching millions worldwide. We warned about vaccine injuries, censorship, and the coming medical tyranny years before COVID-19.

And what did they do? They called us “Conspiracy Theorists,” “Anti-Vaxxers,” and “Killers.” Dangerous.

They said we were killing people with “misinformation.”

Facebook banned us. YouTube deleted our videos. Legacy media ran hit pieces. PayPal froze our accounts.

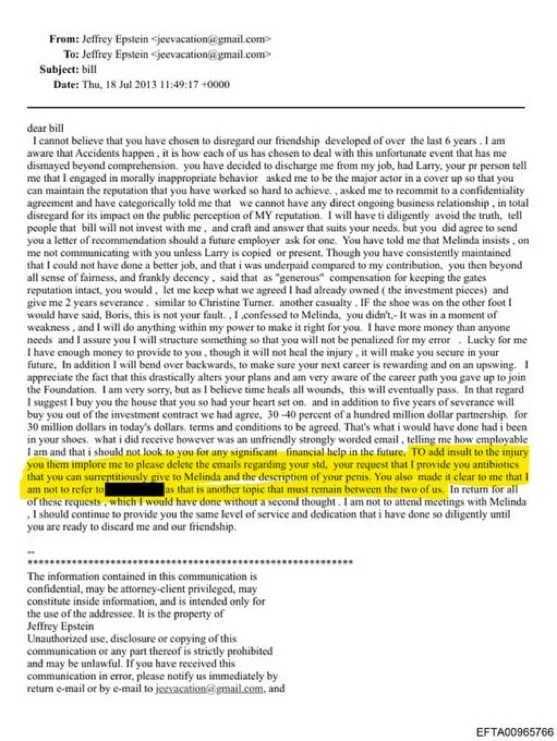

All while Bill Gates—a man with documented ties to Jeffrey Epstein, who flew on his plane multiple times after Epstein’s conviction, who got STDs from Russian girls Epstein provided for him for which Gates asked Epstein’s help getting him antibiotics to slip secretly to his then wife, Melinda, so that she would not know about his inexcusable and perverted escapades—yes, THAT Bill Gates—was at the same time, being platformed on every major news network as the world’s health oracle.

All while Anthony Fauci—who funded gain-of-function research in Wuhan through Peter Daszak and EcoHealth Alliance, who lied under oath to Congress, who flip-flopped on masks, lockdowns, and vaccines—was treated like a saint. Time Magazine’s “Guardian of the Year.”

All while Pfizer—a company with a $2.3 billion criminal fine for fraudulent marketing, bribery, and kickbacks—was given blanket immunity from liability and billions in taxpayer dollars to produce a vaccine in record time with no long-term safety data.

All while Pfizer—a company with a $2.3 billion criminal fine for fraudulent marketing, bribery, and kickbacks—was given blanket immunity from liability and billions in taxpayer dollars to produce a vaccine in record time with no long-term safety data.

Were we the dangerous ones?

No.

We were the truthful ones. And that made us the enemy.

The Weaponized Institutions: From Epstein’s Blackmail to Your Digital ID

Epstein’s operation was never just about blackmail for perversion; it was blackmail for control. The files show his cozy ties to intelligence agencies (Mossad, CIA), financial giants like JPMorgan and Deutsche Bank, and political leaders across the globe.

This is the same cabal now pushing:

The Great Reset

Digital IDs

Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs)

15-minute cities

Carbon credit social scoring

Vaccine passports

Let’s connect the dots they desperately don’t want you to see:

Financial Control:

JPMorgan banked Epstein for years despite clear red flags—over $1 billion in suspicious transactions flagged internally and ignored. They knew. They didn’t care. They paid a $290 million fine and moved on.

Now, banks like Bank of America, Chase, and PayPal de-bank conservatives, truckers, health freedom advocates, and anyone who questions the narrative. Canadian truckers. Gun shops. Crypto entrepreneurs. The goal is the same: punish dissent and control economic life.

CBDCs are the endgame—a digital leash on every citizen. Programmable money that can be turned off, restricted, or expired. Social credit by another name.

Medical Tyranny:

The FDA, CDC, and WHO—utterly captured by Big Pharma—lied about:

COVID origins (Wuhan lab leak dismissed as conspiracy theory)

Vaccine efficacy (”95% effective” turned into “you need boosters forever”)

Natural immunity (ignored despite being superior)

Early treatments (ivermectin, hydroxychloroquine, vitamin D censored and mocked)

They attacked natural health advocates just as they’ve done for decades with cancer cures, detox protocols, and anything that threatens Big Pharma profits. They are not health agencies; they are profit-enforcement arms dressed in lab coats.

Political Corruption:

Epstein’s blackmail ensured elite immunity. His client list includes presidents, princes, CEOs, scientists, and media moguls.

Meanwhile, true dissidents—Julian Assange (tortured in prison for journalism), Edward Snowden (exiled for exposing mass surveillance), and journalists like us—face persecution, imprisonment, debanking, slanderous hit pieces, and/or constant character assassination.

Two systems of justice: one for them, one for you. One for Epstein’s friends, one for truth-tellers.

The Way Forward: They’re Exposed. Now It’s Time to Build.

The Epstein files are more than proof; they are a declaration that the system is rotten to its core. But here’s the beautiful part: they vindicate us completely.

Every warning. Every documentary. Every article. Every post that got us banned. All of it was true.

The globalists’ grip is weakening. The truth—the real, ugly, documented truth—is erupting from the very files they tried to hide. They labeled us liars, but the emails show they were the architects. They silenced us, they censored us, but that only made our voices more necessary.

Epstein did not kill himself. COVID-19 was not natural. The vaccines were not safe or effective. The censorship was not about protecting you—it was about protecting them.

And now? Now it’s time to use this vindication as fuel. Not for revenge, but for revolution. A revolution of truth, health, freedom, and justice.

They tried to bury us. They didn’t know we were seeds.

The Epstein files are a smoking gun. A paper trail. A confession written in emails, financial structures, and offshore accounts.

They prove what we’ve been saying all along:

The system is rigged.

The elites are criminals.

The pandemic was planned.

The censorship was coordinated.

And we were right. 👍

🙏 Donations Accepted, Thank You For Your Support 🙏

If you find value in my content, consider showing your support via:

💳 Stripe:

1) or visit http://thedinarian.locals.com/donate

💳 PayPal:

2) Simply scan the QR code below 📲 or Click Here:

🔗 Crypto Donations Graciously Accepted👇

XRP: r9pid4yrQgs6XSFWhMZ8NkxW3gkydWNyQX

XLM: GDMJF2OCHN3NNNX4T4F6POPBTXK23GTNSNQWUMIVKESTHMQM7XDYAIZT

XDC: xdcc2C02203C4f91375889d7AfADB09E207Edf809A6